Digitizing Fashion: A Supplement, Not a Substitution

COVID-19 hit the fashion industry like any other: with unexpected challenges and thus a need to adapt. Many of the former givens of the fashion industry came under attack. The once traditional (now perhaps antiquated) seasonal fashion calendar is already ridden with problems of sustainability, accessibility and pace. Given many designers’ distaste for the norm, COVID’s limitations coincided naturally with a possible shift in the way that designers share their work. In line with the digitization of most aspects of our lives — work, family, and social — fashion has been increasingly pushed online.

Digital runway shows were created to replace typical fashion weeks, with varying levels of involvement and successes among designers. After the British Fashion Council put forth an online men’s fashion week, The Fédération de la Haute Couture et de la Mode went through with the first online couture fashion week. As designers like Giorgio Armani and Chitose Abe of Sacai dismiss the virtual platforms for smaller scale operations, and Virgil Abloh holds off to display Off-White’s new collections, questions of quality and purpose become central. Are these virtual shows valid substitutes for the treasured yet tried experience of attending a runway show? Will they simply act as placeholders for the fashion world’s typical in-person shows, or is there more promise to their future?

While the answer is not clear, the trajectory seems to be. Technology is working its way into fashion. The uncertainty is in where it will act as an asset. Particularly in the midst of COVID-19, it has become clear that technology can augment fashion in incredible ways. However, digital fashion shows lack the experience that in-person runway shows provide. Technology should be aimed at improving, not replacing, the traditions that exist.

Harnessing the power of technology into fashion is crucial in elevating fashion to its highest potential in terms of creativity, sustainability and accessibility. The necessary changes in practices due to the pandemic seem to have pushed the fashion industry to employ technology to a level we are already seeing in other forms of art. Shows, for example, become more than just catwalks — they are multimedia experiences that go beyond clothing. They look at an entire message in the way a standalone show may not be able to. They may not capture attention like an in-person show, but they bring new depth and opportunity: without typical fashion weeks, formalities loosen. Designers are given a timeframe to present in, rather than a runway to work on.

With fewer guidelines and limited crutches to fall back on, more innovation is possible. Kerby Jean-Raymond of Pyer Moss, for example, announced a drive-in fashion experience rooted in technology to launch the film “American, Also.”

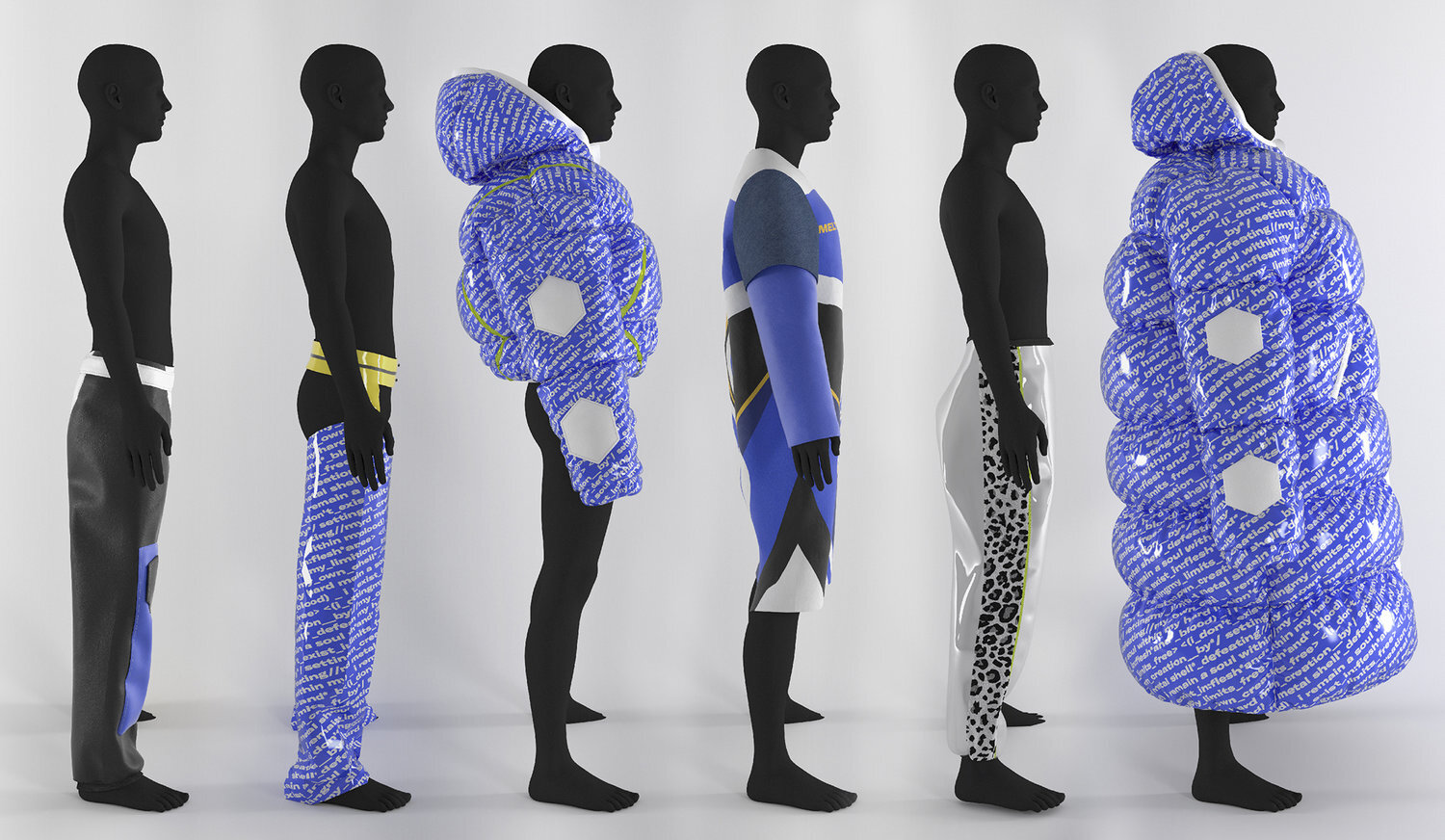

“It’s always been our mission to show the amount of thinking and laboring that goes behind putting together a collection,” Jean-Raymond told Vogue. The new context made that plan possible in a way that it was not before. Some designers have started rethinking content and manufacturing altogether. The brand Hanifa’s virtual fashion show, for example, left behind the entire context of a runway — the models, the audience, the platform — and simply centered renderings of clothing, concepts more than materials.

The technology used in Hanifa's show — 3D imaging, CGI, and different rendering and body-mapping — have seen an uptake in its employment in fashion. This technology, mainly born from gaming, is expansive. Gayle Dizon of creative production company Dizon, explained that online shows do not only breach concerns surrounding venues and timing, but eliminate the ceiling altogether. He told Vogue that he posed a prompt to his team: “Let’s start ideating on our dream scenario. Where would you do a show if you had no constraints of time, space, or location?” The answer was now a possibility. Combining technology with the fashion world, from digital backdrops to rendered clothing, we now know, opens an indefinite number of doors.

There are also the obvious advantages to online shows. The fashion world has been looking to produce less and better in terms of quality and ethics, as the speed at which it now moves cannot be maintained ethically. With a looser definition of production, this may be possible. Virtual content like rendered clothing can fill some of the demand for constant material intake. Along with supplementary media supporting the larger message of a collection, ideas and labor can be used more sustainably as well. Stockholm’s fashion week, previously economically and environmentally unsustainable, will be able to run virtually because of these changes. The change frees the rules of traditional runway shows and gives both organizations and designers a chance to reimagine the potential of sharing fashion.

“I have always wanted to use alternative formats to communicate my creative process to an even wider audience,” Alessandro Sartori of Ermenegildo Zegna wrote. “The idea that I will present the collection with a digital tool gives me great energy and freedom of thought because I can finally enter directly into people’s place.”

Digital shows make high fashion more accessible; there’s no reason these shows now cannot be open to a much wider if not unlimited audience, creating an artistic dialogue in touch with a larger group of consumers. While this new potential has come through in virtual progress that we have seen, it has been more a factor of crisis than it is technology. It should not have taken COVID-19 to welcome these much-needed changes in the fashion industry, but the redefinition of connectivity has certainly propelled them.

Despite the definite potential that the fashion-tech duo provides, the trend will fade if virtual runway shows simply emulate physical ones. First, there are enough problems with the lack of representation in fashion, without getting rid of the way that the art centers around people altogether. Second, the accessibility they could provide is shallow. More people may see the clothing walk the runway, but the prices and concepts are still exclusive and high. Most importantly, though, “phygital” runways lack the sensory experience that in-person shows provide. Part of fashion’s appeal is the way that a piece’s beauty centers the human form. The president of the Fédération de la Haute Couture et de la Mode spoke to the missing component, saying “nothing will ever replace the unity of time and place. Shows are a major component of the fashion industry and this will remain.” There is an element of connectivity in every aspect of our lives that is lacking in virtual replacements, and fashion is no different.

Lighting and runway designer Thierry Dreyfus strongly affirmed this sentiment: “fashion is about experience. … We’ve seen life through screens: flat. No taste, no smell, no emotions,” Dreyfus told Vogue. “Screens, I insist, [have] no emotion.”

Fashion, though, like any form of art, has incredible emotional power. As much of the employed technology comes from the gaming industry, where visuals tend to be realistic but perhaps off-putting, a remedy seems unlikely.

While Dreyfus pointed to this disconnect as a reason to stick with the norm, Dizon noted that this challenge could be another opportunity to innovate: “the idea of a poetic, virtual fashion space online does provide a thrilling challenge for the fashion industry. Science fiction and video games have long been a vehicle to build a utopia, hinging on the idea that beyond our physical realities we can build something better. Can virtual fashion do the same?”

Digital reality opens untapped potential for more conceptual fashion, at the expense of distancing that work from the general public. Making the connection and emotion that we expect in fashion a priority online could bring realism into our dream world in a way that would revolutionize the fashion world.